By Coptic Solidarity –

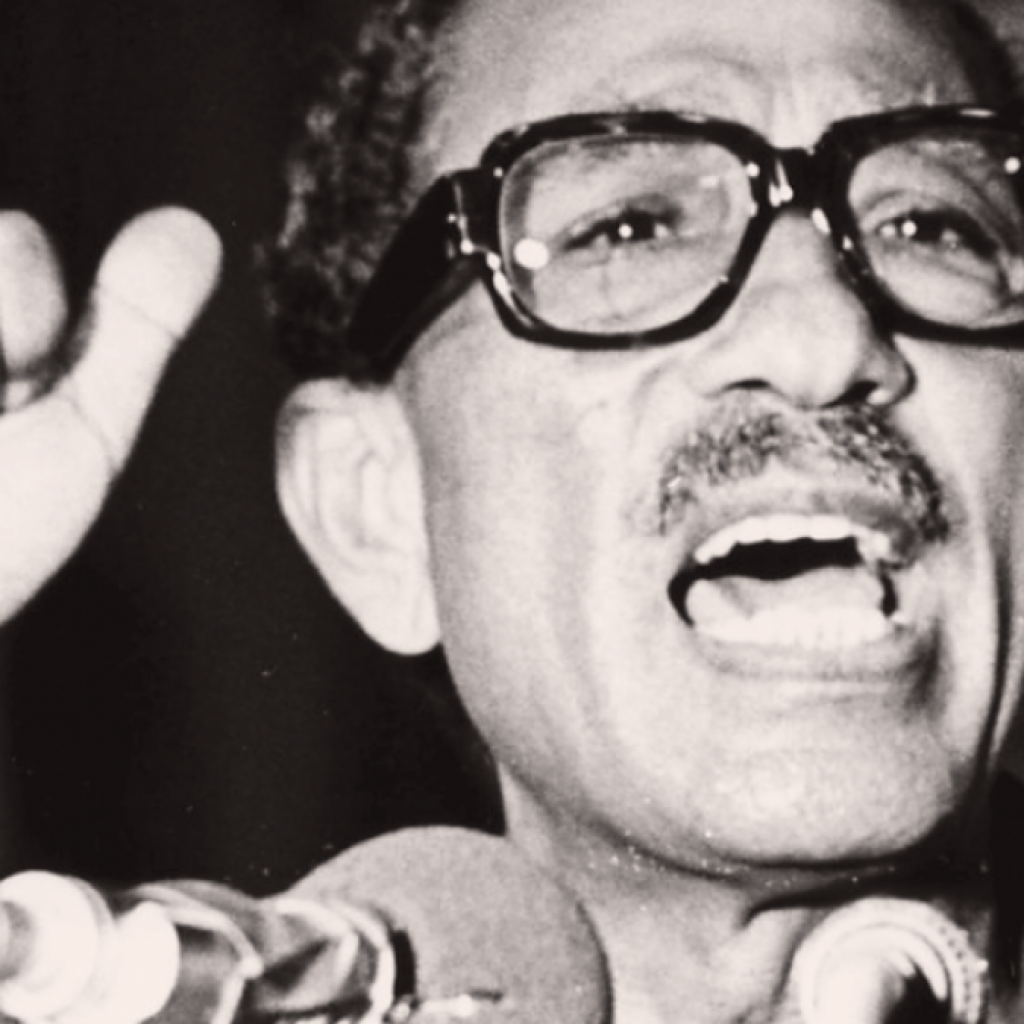

On the tenth anniversary of the departure of Pope Shenouda III, here are excerpts related to his years on the St. Mark Seat, taken from Adel Guindy’s book “A Sword Over the Nile – A Brief History of the Copts Under Islamic Rule” (Austin Macauley – New York, June 2020)

***

On November 14th, 1971, Shenouda III became the 117th pope. Barely six months later, church and state came into conflict. A prayer hall belonging to the Bible Friends Association was used as a church without a formal permit in the Cairo suburb of Khanka, and after ‘unknown’ people set it ablaze, the police moved in and knocked the building down. The day after, Pope Shenouda ordered bishops and monks to go to the ruins of the church and celebrate mass there, even if they risked being shot at and killed. The police tried to stop them, but they went on. Sadat was dismayed—and no wonder! For the first time since the Arab-Islamic invasion, a Coptic Pope was prepared for such an open challenge. He determined to have a show down, considering that, “Shenouda has gone beyond everything,” and was threatening, “I am not going to take anymore [..]. I can’t carry on with this time-bomb ticking away underneath me.” Finally, he was advised to calm down and to ask the parliament to investigate the whole matter.

A committee, chaired by Deputy Speaker, Dr. Gamal Oteifi, investigated the issue and duly reported in November, 1972. Rather honestly, the committee concluded that, “Unless we address the roots of the problem, probe the factors that lead to it, and come up with a remedy, the follow-up efforts will stop when things calm down.” It continued that there was a need to find a permanent solution in place of the temporary sedatives which threaten the recurrence of the hidden disease that will become more serious and fatal.” Among other recommendations, the committee highlighted the need to abolish the Khatt-i Hamayuni and replace it with a simpler regulation that would not require a presidential decree for every church. Later, in 1973, Sadat met with the Pope and the Synod, and said that he would authorize 50 new churches a year. (In retrospect, the promise was never kept, and he specifically refused to authorize a church in Khanka).

In 1976, Sadat ordered a review of all existing laws to ensure their compliance with Sharia. The committee, headed by speaker, Sufi Abu-Taleb, himself a strong proponent of applying Sharia, considered also to issue a law on riddah, whereby anyone who apostatize from Islam would be given one chance to repent and return, but if he persisted in his apostasy, he would be hanged, and only two witnesses would be needed to convict him. There was talk of putting into practice the strict Sharia punitive code (Hudud) which ordained that a thief should be punished by having his hand amputated. Some judges were so enthusiastic that they began to pass judgment according to Sharia rather than civil law.

As was to be expected, all the talk about the necessity for all citizens, Muslims and Christians alike, to conform to Sharia had profound repercussions in the Coptic community. Other intimidating—to say the least—measures included persistent articles by senior Azhari Sheikhs, in the state-owned flagship newspaper Al-Ahram, depicting the Bible as ‘adulterated,’ accusing Christians of ‘Shirk and Kufr—the two worst crimes in Islam’s eyes—and calling for decisive victory by Muslims over the Kuffar. Another bit of ‘information’ aggressively diffused in the media was a government census giving the number of Copts to be slightly over two-million, out of a total population of thirty-seven-million. The new National Assembly (350 members) had only one, appointed, Copt.

On January 17th, 1977, a Coptic conference, echoing the one of 1911, was held in Alexandria and ended by producing a communiqué which was never openly published:

“Circumstances have made necessary the calling of a conference of the Coptic people in Alexandria [..] His Holiness, Pope Shenouda III, attended the opening meeting on 17th December, 1976, in the great Cathedral of Alexandria. The conference proceeded with a discussion of the problems on the agenda, and took into consideration the work of the preparatory committee, which met on fifth and sixth July. All members of the conference, clergy and laity alike, agreed on two propositions which, in their opinion, could not be separated from each other. The first is an unassailable belief in the eternal Egyptian Coptic Church, founded by Mark, the evangelist, and sanctified by the sacrifices of martyrs through the ages. The second is the sense of responsibility toward the Fatherland, for which we are ready to sacrifice our lives, and in which the Copts represent the most ancient, pure, and authentic element. No people are more attached do the soil all Egypt, or prouder of their country and their nationality, than the Copts.”

The communiqué referred to the most serious issues of freedom of belief and stated that ‘freedom of belief means that every human being is free to embrace the religious belief in which he believes and not to be harmed or to suffer because of this belief. However, some trends that are against the freedom of Christian faith, and regrettably, followed by some official bodies, such as the directorates of security, the administration of civil status registry, notary offices, and personal status public attorneys; in cases of conversion to Islam on the one hand, and the cases described as apostasy from Islam on the other hand.’ It then called for the freedom of religious practice, the protection of the family and Christian marriage, equality and equal opportunity (in jobs), the (adequate) representation of Christians in parliamentary bodies, and ‘warning against extremist religious trends.’

The conference called for abolishing the draft apostasy law, abandoning the thought of implementing laws derived from Islamic law on non-Muslims, the need for firm intervention by government authorities to eliminate extremist religious trends, and demanding the lifting of official or disguised censorship of Christian publications, putting an end to writings attacking Christian belief, and to include in the curricula of historical, literary, and cultural studies in the various stages of education and in the universities, regarding the Christian era in the history of Egypt for six whole centuries before the Islamic conquest.

The conference was the most serious gathering of its kind since ‘The Coptic Conference’ held in Assiut, in 1911—with one big difference: it was sponsored by the Pope, no less, whereas the then-pope had opposed the previous one. To conclude, it suggested that 31st January to 2nd February, 1977, should be a period of fasting for all the Copts, and that the conference would remain in session until its resolutions had been implemented. The conference had received messages of support from Copts abroad.[1]

For once, there was a courageous Patriarch willing to stand up for the rights of his suffering community.

In April, Shenouda was the first Pope to visit North America, where he spent 40 days in U.S. and Canada. He met with President Carter who greeted him as the spiritual leader of ‘seven million’ Copts — a remark that enraged Sadat even more.

Sadat, meanwhile, stopped talking about the proposed Sharia laws. But as a counterblast to the Coptic Conference, the rector of Al-Azhar, Sheikh Abdul Halim Mahmoud, convened a conference of Islamic organizations in July. This conference issued a series of resolutions: any law or a regulation which runs counter the teachings of Islam should be treated as null and void, and should be a rejected by Muslims. The application of Sharia is mandatory and not the consequence of parliamentary legislation, for there can be no questioning Allah’s law. The delay in enacting true Islamic legislation is due to appeasement of non-Muslims, and the parliament should, without any further delay, pass the legislation which has been already tabled. The conference declared its appreciation of the recent speech by the president in which he spoke of his intention to purge the state machinery of atheists. The conference also appealed to the president to ensure that religion (Islam) should be made the basis of all education.

On the eve of the Coptic Christmas, January 6th, 1980, bombs exploded at a number of churches in Alexandria, and when the government did not move to apprehend the perpetrators, Pope Shenouda decided to take a public stance. On 26th March, 1980, the Pope held a session of the Holy Synod, after which a stern statement was issued: “Having studied the situation of the Copts and the numerous complaints that they made from all the governorates across Egypt, and complaints by the Coptic students inside and outside university cities (dorms); what the Copts are subjected to by way of insults and accusations of Kufr, as well as different kinds of incitation and attacks on their lives and churches, the kidnapping of Christian girls and converting some of them in various ways; the Holy Synod decided to cancel the official celebrations of the glorious Easter this year (to be celebrated on April 6th), limiting them to prayers in the churches, while not accepting the congratulations of the feast, as an expression of the sufferings by the Copts.” The members of the Holy Synod also decided to retreat in monasteries during the feast. The statement was to be sent to the priests of the churches of Cairo, to read out to the congregation at the end of the Palm Sunday and of Good Friday prayers. The statement also noted: not to put decorations on the facade of the churches and not to accept congratulations on the eve, or the day, of Easter.

On May 14th, Sadat gave address to parliament, in which he said he had knowledge of a ‘plot by Shenouda to become a political as well as religious leader of the Copts and set up a separate Coptic State with Assiut as its capital.’ “But the Pope must understand,” he said, “that I am the Muslim president of a Muslim country.” He told one of his aides that he considered sacking the Pope by means of a plebiscite. Apart from the preposterous accusations, it is, to say the least, alarming to think what the repercussions would have been—based on the precedent of the preceding history—if a plebiscite had been held in a predominantly Muslim country to determine the fate of the head of the Christian church there.

June, 1981, saw the most serious ‘clash’ for many years. In the Zawya al-Hamra popular quarter of Cairo, what ‘started as a quarrel between neighbors turned into an armed battle’ (as the police reports put it). Once again, the origin of the dispute was to be found in the ‘illegal’ setting up of a church, with members of the president’s National Party trying to prove their religious zeal by using force to stop its construction. The government said that seventeen Copts were killed and 54 injured, but a few months later, it became widely known that the real number of victims was 81.

During a visit by Sadat to the U.S. in August, the Coptic community took half-page advertisements in the Washington Post and the New York Times, listing their grievances, and staged two demonstrations in Washington. These took place in spite of the fact that Pope Shenouda had sent Bishop Samuel in advance of the visit, asking the community to lie low and not provoke him.

On September 3rd, Sadat arrested many of his political opponents. He also arrested 170 Copts, both clergy (including eight bishops and 24 priests) and laymen, and ordered the closure of Al-Kiraza, a bi-weekly church publication, as well as Watani, the only Coptic newspaper in Egypt. Two days later, Sadat announced in a televised speech the ‘annulment of the government’s recognition of Pope Shenouda,’ effectively suspending him from his administrative functions which were transferred to a Patriarchal committee of five bishops, including Bishop Samuel. The Committee declared (on September 22nd) that the “Coptic Church, according to its sacred evangelical teachings and ecclesiastical laws, is committed to obedience to the ruling authorities, in accordance with the Holy Bible, ‘every soul is subject to the superlatives.’”

The doors of the Monastery of Abba Bishoy, where the Pope was in retreat, were shut on September 5th, and troops surrounding it stopped all movements to or from it. A month later, on October 6th, 1981, Sadat was killed, (as well as Bishop Samuel, who was on the same parade tribune). For most Copts, this was a prompt divine judgment.

***

Hosni Mubarak became president, but despite numerous demands, especially by Coptic diaspora, he left Pope Shenouda under confinement in the monastery for a total of 40 months. On January 5th, 1985, the Pope was released after 1213 days, and a presidential decree formally reversed the one made by Sadat.

Following Sadat’s assassination, the first period of Islamic Jihad’s armed conflict in Egypt came to an end. By the 1990s, the second phase began, including a long series of terrorist operations against the Copts, the government, and tourists. This phase ended with a terrorist attack targeting tourists in Luxor in November 1997.

Then came the phase of the ‘ordinary people’ attacks against Copts. Mubarak’s era was marred with homegrown violence that rather came from individuals not belonging to or acting on behalf of a particular terrorist group. It was common in these cases that no specific perpetrators are named, and the criminal charges thus become ‘diffuse.’ Thus, the aggressors have rarely been brought to justice, nor has any condemnation ever been issued. This was also the result of the security apparatus’ failure to handle and process criminal evidence appropriately. Reason for mob attacks could be discovering a place where some Copts were ‘praying without permit.’ Another reason would be a case of a Coptic man accused of having a relationship with a Muslim girl. The opposite would, of course, be fine, and even encouraged; scores of Coptic girls every year, often underage, are lured and converted to Islam, with the full complicity of the police, and other authorities.

State-sponsored Islamization of the society continued and intensified. This strategy employed by the regime had attempted both to satisfy and keep the Islamists in check by offering them a formula in which the state continued to rule from the top while the radical Islamists determine and supervise social norms. Islamization penetrated the media, education, and the state infrastructure. Throughout the process, the regime took action only in cases that threatened its own stability, tolerating, if not encouraging, the oppression of Copts. The ‘Islamic street’ grew stronger and kept demanding greater Islamization, and the regime met these demands in order to increase its own legitimacy, power, and domination. In addition to the Muslim Brotherhood, Salafist groups became ever more present.

In fact, fighting sectarian strife was not the political priority for the regime because it was not perceived as a threat to its survival; consequently, the crucial state agencies (local administration, police, state security, and so on) were never instructed to adopt a consistent strategy against it. The authorities’ typical approach was to procrastinate and take the path of least resistance; logically, this usually consisted in appeasing the Muslim majority.

Violence against the Copts was, and continues to be, only one facet of systematic discrimination they face. The situation has even been described as one of ‘daily martyrdom.’ In the words of a Copt whose brother was killed in one of the attacks, “We all envy those martyrs. They escaped the humiliation that we endure [..] the Lord saved him from the miserable treatment and loathing the rest of us get.”

In the judiciary, some judges ignored existing civil laws and ruled according to Sharia (referring directly to Article II of the constitution). In one typical incident, the Administrative Court rejected a lawsuit by a Copt, contesting the state changing his religion to Islam after his Christian father had converted when he was seven years old. The ruling rejected his demand (thus, the man was considered to be a Muslim because his father had converted), and stated that he could not ‘convert’ to Christianity since conversion was only permissible if it followed a certain order ‘sanctioned by the Almighty Allah: he who believes in Judaism is called on to embrace Christianity, and he who believes in Christianity is called on to embrace Islam, the seal of all religions. In all these cases, the opposite is incorrect, as evidenced by Allah’s ordering of the revelation of His religions, and in accordance with public order and morals in Egypt.’

Mubarak’s era saw numerous massacres against the Copts, the last of which took place in Alexandria less than a month before a popular uprising that ended with toppling his regime. Under Mubarak’s watch, some 324 incidents of sectarian attacks (i.e., excluding common law crimes) took place against Copts ‘for who they are.’ These resulted in 157 persons killed, over 800 wounded, and 103 churches attacked or burnt, as well as burning, looting, or ransacking of properties or businesses belonging to 1380 individuals. Perpetrators have very rarely been prosecuted, let alone condemned by a court. Most significant among them were al-Kosheh massacre in January 2000 (20 killed). In 2010, several incidents took place, in Nag-Hammadi (7 killed), Matruh, and Omraneya.

Other forms of discrimination against the Copts and their alienation continued with little improvement. At one time, the president’s party, which typically holds the crushing majority of the parliament, did not even bother to propose a single Coptic candidate in the parliamentary election of 1995. The total number of Copts in Mubarak’s seven parliaments averaged eight (including those appointed), at an average percentage of 1.7 from the total.

***

The Republican regime (since 1952) never tried to compensate for the initial under-representation caused by the low percentage of Copts in the upper ranks of the military. Thus, the situation was perpetuated through a mixture of tolerated individual discrimination, ceilings for Copts’ representation in certain areas, as well as career choices among the Copts themselves influenced in turn by the anticipation of discrimination. The fact is that the underrepresentation of the Copts was never addressed during the Mubarak era (in fact, the regime consistently denied the existence of discrimination).

The oft-bemoaned Coptic retreat to the community sphere and the political role of the Coptic Orthodox Church were a clear consequence of all this political marginalization.

Signs of cultural exclusion, if not persecution, permeate the state’s policies.

(…)

***

For at least one decade after the release of the Pope by Mubarak from his ‘monastery confinement,’ the President and the Pope maintained an arms-length distance, but without confrontations. Over the years, some kind of entente was established, and the Pope became more mellowed and even a supporter of Mubarak’s regime in its last years. Some say that this was a mere window-dressing aimed at giving an impression of harmony, but devoid of any genuine ability to achieve structural changes. It is certainly true, but the dilemma facing the Pope, and indeed the international community, was that Mubarak presented the political options in a binary way: “Either me, or the Islamists.” The Pope probably preferred ‘the devil we know.’ He did, however, continue to relentlessly endorse Coptic civil and citizenship rights. When asked (even on state T.V.) why wouldn’t he rein in Coptic activists abroad who criticize Mubarak, his answer would typically be two-folded: “They live in free countries where they enjoy their freedom of speech and hence (he) could not muzzle them,” and, “The best way to avoid their critiques would be to resolve the problems so that there would be nothing to complain about.”

The assertive adoption of Coptic demands by the church leadership and the activities of expatriate activists started in the 1970s. This was followed by an intermediate course steered by the church between the accommodation and assertiveness became the dominant form of Coptic public expression throughout the 80s and early 90s.

***

The tipping point came on 2011’s New Year’s Eve, when suicide bomber killed 23 worshipers and wounded 97 in the Two-Saints Church in Alexandria. The government was quick to blame the Mossad (the Israeli secret service) and Al-Qaida. This time, the public fury came from Copts, as well as from Muslims.

The breakdown of the Mubarak regime (February 2011) immediately caused a state of insecurity and anxiety that deeply affected large parts of the Coptic community and made them more pessimistic than never before. On the other hand, Coptic activist circles achieved an unprecedented degree of mobilization that culminated in several large demonstrations and sit-ins in central Cairo. As a result, public and official reactions to incidents of sectarian violence were more sensitive to Coptic demands than ever before.

These openings did not last long. The growing Coptic rights movement on the streets by youth Copts was a significant development. But it was confronted and bloodily repressed by the army on October 9th, 2011, in the Maspero massacre where 28 Copts were massacred.

The political scene was dominated by bitter power struggles between the Military Council, the revolutionary street, and different political camps and the state bureaucracy and judiciary. The Muslim Brotherhood achieved their decades-old dream of taking over the rule, with the implicit but unmistakable support of the Military Council, when their candidate won the presidential election and their party the parliamentary. However, in their greediness, the Brothers overplayed their hand and thought that they could monopolize the rule, dismissing the understanding that the army would continue to hold the ‘power’ behind the rule. The bras de fer quickly ended with an army-backed street ‘revolution’ that toppled the Brotherhood’s rule on July 3rd, 2013. The Brothers’ revenge targeted the Copts, when massive simultaneous attacks on August 14th resulted in the burning of 43 churches and dozens of Christian religious institutions and schools, and Coptic-owned businesses and homes. This was the largest and most widespread series of attacks since that of May 16th, 1320, under the Mamluks. It was also quite rightly called ‘Egypt’s Kristallnacht.’

The army quickly imposed the upper hand, in a barely disguised alliance with Salafi Islamists, adopting the ‘Pakistani model’ of the turban-helmet alliance. The new regime lead by El-Sisi, president since June 2014, is hence by no means less Islamic than that of the Brotherhood, if not more.

***

On March 17th, 2012, Pope Shenouda III passed away, aged 89, after a reign of over 40 years. In an unprecedented scene, hundreds of thousands of Copts closed the streets around the Cathedral in Cairo where his funeral was held.

He is remembered as probably being the most visible Pope in the history of the Coptic Church. Bold and critical, he knew when to be conciliatory and when to be outspoken, as he had no intention of suffering in silence. (…)

Footnotes can be found in the book, which may be found at various outlets, such as: https://www.amazon.com/Sword-Over-Nile-Adel-Guindy/dp/1643787608/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1647117091&sr=8-1