By Hannah Srour-Zackon –

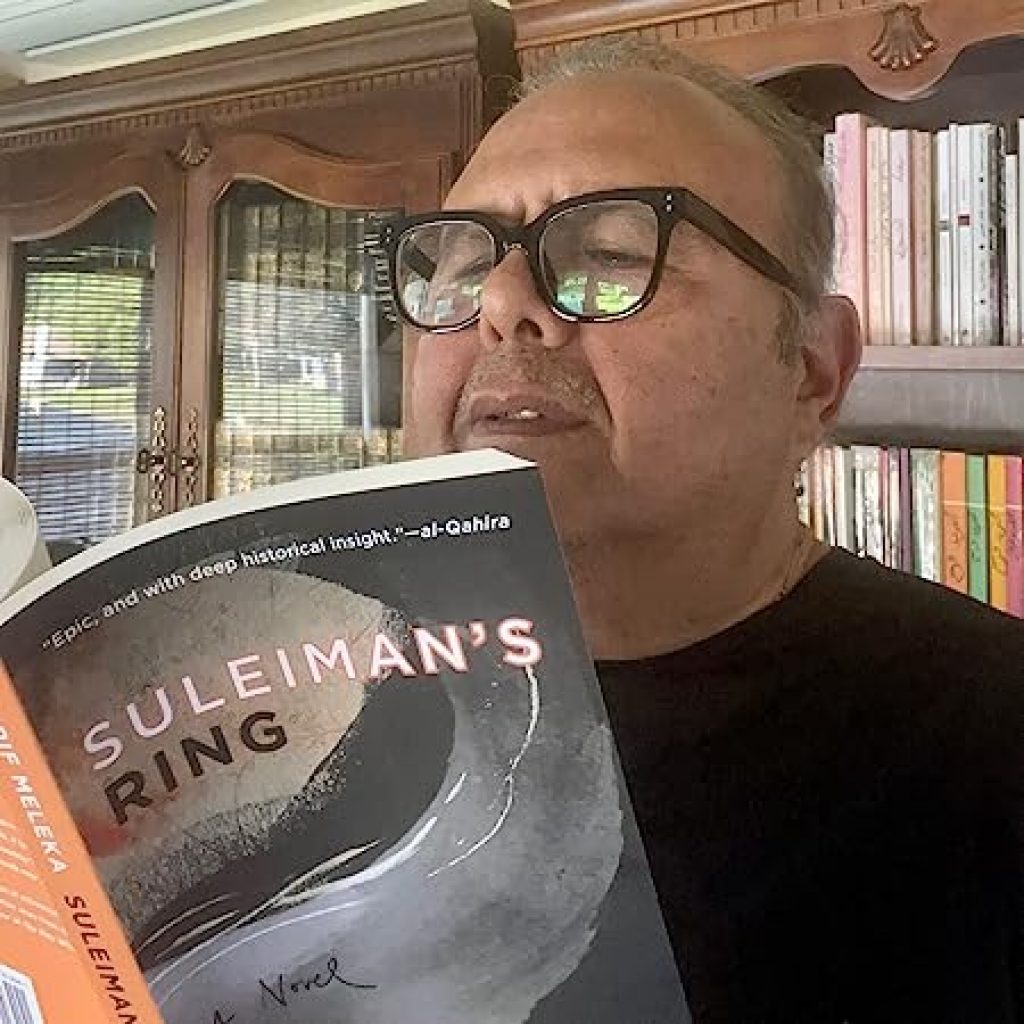

Sherif Meleka’s epic novel Suleiman’s Ring uses the Biblical characters of David and Solomon to explore the persecution and expulsion of Jews from Egypt. It is set in mid-20th century Alexandria. Originally published in Arabic in 2008, it is now available in English translation.

What if the fabled Seal of Solomon—an item of mystic importance in both Jewish and Muslim myth—were a real object located in Egypt? What impact would it have during the country’s politically tense post-revolution era?

This is the central conceit of Sherif Meleka’s dazzling epic novel Suleiman’s Ring, set in mid-20th century Alexandria, which was originally published in Arabic in 2008. Now, thanks to the translation work of Raymond Stock, it’s been published as his English-language debut.

Meleka evokes the biblical figures of David and Solomon in his protagonists—Daoud and Suleiman, respectively—and puts their Jewishness at the centre of the story. Through them, he explores the persecution and expulsion of modern Egypt’s Jews.

Suleiman’s Ring also mulls over what destiny, fortune, and identity mean for both the individual and the nation during some crucial moments.

Daoud Abdel-Malek is an oud player who possesses a magical silver ring, said to give its wearer with strength and protection. The main drama begins when he is summoned, along with his dear friend Sheikh Hassanein, to meet with Gamal Abdel Nasser. Daoud temporarily gifts him his ring so that he may have good fortune in the brewing revolution.

Although the revolution succeeds, warring political factions become locked in a complex battle over the future of the newly independent Egypt, while meanwhile waging war against the newly formed State of Israel. Consequently, Daoud’s place as a Jew in his own society falls under suspicion. Members of various political factions, including the government and the competing Muslim Brotherhood, address him as Khawaga (foreigner) and demand he leave his native land, seeing his Jewishness as a threat.

Told from various perspectives and imbued with magical realism, the novel makes for an allusive reading experience. Daoud, like his biblical namesake, is musically talented, poetic, and highly introspective. Yet he also suffers from similar flaws. This becomes apparent in the parallel to the story with Batsheva.

He also shows favouritism toward his son Suleiman (born to his third wife, a Christian woman), even though he is not his firstborn son, and intends to gift him the ring as his birthright. As the book shifts focus to Suleiman midway through, we get to know a man revered for his sagacity, but suffering from the same weakness for women as the biblical Solomon.

Meleka’s writing in translation is poetic and beautiful, evoking the language of the Book of Lamentations. The way he writes about Daoud’s relationship with Alexandria is reminiscent of biblical writings about Jerusalem—as though the city itself were a beautiful woman to be cared for. Indeed, of all the loves in Daoud’s life, Alexandria is the greatest. This is why being suddenly seen as a foreigner is so painful. His ties to the city go back generations—to the time of the Pharaohs—and the despair he feels is profound. Indeed, he can hardly comprehend when his two oldest sons leave for Israel.

The novel is also a lament for free speech and tolerance. In one particularly poignant passage, Daoud ruminates on the intermingling of Jews, Christians, and Muslims in Egyptian society and how they are separate only at worship and death. This co-existence falls apart as the story unfolds and Daoud becomes increasingly suspected of dual loyalties.

On a personal note, I must confess that I found it a deeply moving read, given that my own grandparents were among the Jews of Egypt who were expelled during this time. It brought out, for me, the emotional pain they may have experienced—while its loving description explains why a nostalgia still remains for many.

At this time of year, as Jewish communities prepare for Passover, we mark our biblical exodus from Egypt and emergence into nationhood. Suleiman’s Ring is a timely read, not just for its powerful depiction of Jews in modern Egypt, but for its exploration of themes of nationhood, societal divisions—both along political and identity lines—and the influence that individuals can have on an entire society.

____________________