By The New York Times –

Dressed in military fatigues, the gunmen waved down the bus filled with Christian pilgrims as it wended its way down a dusty side-road in the desert of western Egypt, headed toward a monastery.

Claiming to be security officers, the gunmen ordered the passengers to get out. They separated the men from the women and children, and instructed them to surrender their mobile phones. They told the men to recite the shahada, the Islamic declaration of faith.

When the men refused, the gunmen opened fire.

At least 28 people were killed, several with a single shot to the head, according to the Egyptian authorities and relatives of the victims, several of whom were children.

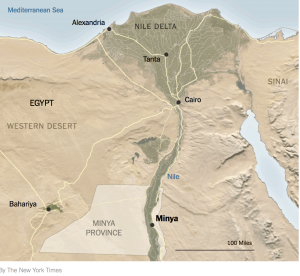

The attack on Friday in Minya Province, 120 miles south of Cairo, was a coldblooded escalation of sectarian violence targeting minority Christians that has left more than 100 people dead since December and shaken the country’s government.

There was no immediate claim of responsibility in the latest assault. Yet it bore the hallmarks of the Islamic State, which in the past six months has dispatched suicide bombers into crowded Sunday services and caused an entire community in northern Sinai to flee their homes in panic.

The Egyptian response came hours later. As President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi delivered a speech from the presidential palace warning that the attack on Christians “will not go unanswered,” the military announced that Egyptian fighter jets had carried out airstrikes on several militant camps inside Libya. In eastern Libya, a military force led by Gen. Khalifa Hifter, a close ally of Egypt, said it had taken part in the air raids, Reuters reported.

Some of the attacks hit the town of Derna, a base of several Islamist militias. It was not the first such reprisal. Egypt also hit targets in Libya in 2015 after militants beheaded 21 Coptic Christian migrants.

Still, the attacks on Libya hinted that the gunmen responsible for the latest violence could have come through Egypt’s western desert — a potentially new flank in a war that has until now centered on Sinai in the east of the country.

In staging the Minya attack, at least seven armed assailants, some masked, lay in wait for the victims on a sandy road leading from a busy highway to the Monastery of St. Samuel the Confessor, which is home to about 100 monks. They attacked three vehicles traveling in convoy — two buses carrying worshipers from the nearby province of Beni Suef, and a pickup truck carrying laborers, all headed to the monastery.

Among the first to die were the drivers, like Atef Mounir, a 62-year-old construction worker who was shot in the head. His nephew David Gamal recounted Mr. Mounir’s death based on the testimony from survivors of the attack.

“They said the terrorists made a group get out of their vehicles and took their phones,” he said, speaking from the hospital where he had come to identify his uncle’s body. “Then they shot everyone.”

Peter Edwar, a Christian activist who was among the first on the scene, said some men had been forced to say the shahada. Some witnesses reported the militants filmed the entire attack. Not everyone was forced out of their vehicles, which appeared to explain how dozens had survived.

“By the time they killed half of the people, the terrorists saw cars coming in the distance and we think that that is what saved the rest,” said Magdy Malek, a lawmaker in Minya who visited victims of the attack on Friday. “They did not have time to kill them all. They just shot at them randomly and then fled.”

The wounded were rushed to hospitals in Minya where doctors scrambled to save their lives. The medical staffs also had to contend with the anger and grief of hundreds of people searching for news about their relatives.

“Everyone is trying to identify the dead and wounded,” said Bishop Makarios, the leader of the Copts in Minya. “There is no time for anger yet.”

The attack was the latest crisis for the bishop, an outspoken critic of Egyptian security lapses in previous violence in Minya, a governorate straddling the Nile where about one-third of the population is Christian, the highest proportion in Egypt.

There have been regular spasms of anti-Christian violence in the area, often triggered by tensions over the building of churches and underpinned by deep-rooted prejudices on the part of Muslim officials and the police.

But Friday’s attack suggested something new: that Christians in Minya are now vulnerable to attack by organized militant groups using the vast western desert as a staging ground.

In its determination to kill Christians, whom it gleefully terms as its “favorite prey,” the Islamic State has underscored its intent to wage a war of sectarian bloodshed in Egypt akin to the one it inflicted on Syria and Iraq.

Experts say the group is highly unlikely to get that far in Egypt, where Mr. Sisi remains firmly in control. Yet the attacks have badly rattled Egypt’s Christians, who account for about one-tenth of the country’s 92 million people, and raised urgent questions about Mr. Sisi’s ability to stem the violent tide.

“It shows a new focus on a soft targets for maximum carnage,” said Mokhtar Awad, an expert on Egyptian militancy at George Washington University. “Islamic State in Egypt is benefiting from new dedicated leadership and improved capabilities.”

The attack on Friday drew wide international condemnation. President Trump issued a statement decrying the “merciless slaughter of Christians” and vowed to crush “evil organizations of terror.” The United Nations and Israel spoke out, as did Hamas in the Gaza Strip and Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Mr. Sisi is not lacking for powers to battle the Islamic State. After the last attack in April, when suicide bombers struck churches in Alexandria and Tanta on Palm Sunday, Mr. Sisi imposed a state of emergency across Egypt that is still in force.

The new measures give him new powers to silence the press and have accused terrorists tried in special courts. For all that, Christians are increasingly frustrated and worried by his failure to protect them, and some are considering moving abroad.

_________________

By Declan Walsh, Nour Youssef.

Photo: Relatives mourned on Friday during a funeral service for some the victims of an attack by armed militants on a Coptic Christian caravan near Minya, Egypt. Credit Amr Nabil/Associated Press