By Jasmine Taylor-Coleman – BBC News –

“They said, ‘You are a savage and dangerous woman.’

“I am speaking the truth. And the truth is savage and dangerous.”

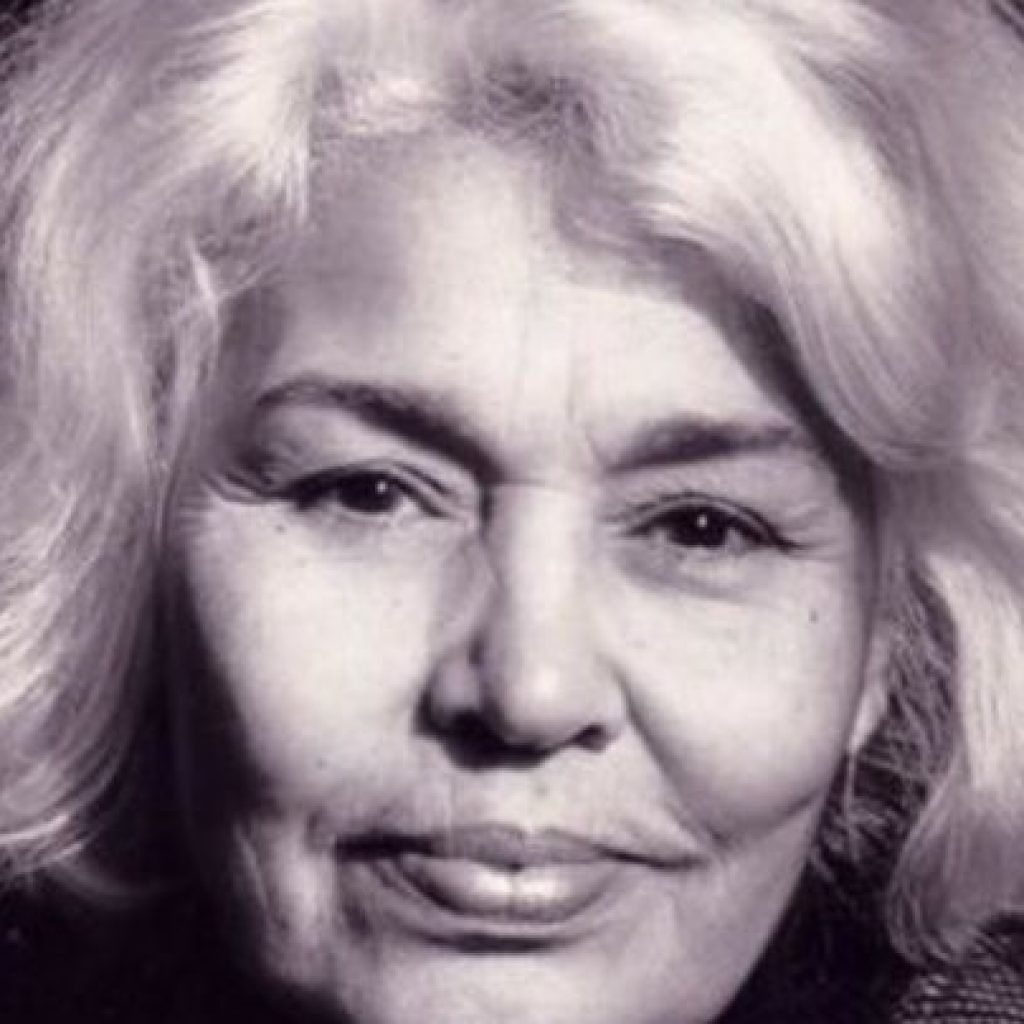

So wrote Nawal El Saadawi, who has died at the age of 89, according to Egyptian media reports.

The pioneering Egyptian doctor, feminist and writer spent decades sharing her own story and perspectives – in her novels, essays, autobiographies and eagerly attended talks.

Her brutal honesty and unwavering dedication to improving the political and sexual rights of women inspired generations.

But in daring to speak dangerously, she was also subjected to outrage, death threats and imprisonment.

“She was born with fighting spirit,” Omnia Amin, her friend and translator, told the BBC in 2020.

“People like her are rare.”

Born in a village outside Cairo in 1931, the second of nine children, El Saadawi wrote her first novel at the age of 13. Her father was a government official, with little money, while her mother came from a wealthy background.

Her family tried to make her marry at the age of 10, but when she resisted her mother stood by her.

Her parents encouraged her education, El Saadawi wrote, but she realised at an early age that daughters were less valued than sons. Later she would describe how she stamped her foot in fury when her grandmother told her, “a boy is worth 15 girls at least… Girls are a blight”.

“She saw something wrong and she spoke out,” says Dr Amin. “Nawal can’t turn her back.”

One of the childhood experiences El Saadawi documented with uncomfortable clarity was being subjected to female genital mutilation (FGM) at the age of six.

In her book, The Hidden Face of Eve, she described undergoing the agonising procedure on the bathroom floor, as her mother stood alongside.

She campaigned against FGM throughout her lifetime, arguing that it was a tool used to oppress women. FGM was banned in Egypt in 2008, but El Saadawi condemned its continued prevalence.

El Saadawi graduated with a degree in medicine from Cairo University in 1955 and worked as a doctor, eventually specialising in psychiatry.

She went on to become director of public health for the Egyptian government, but was dismissed in 1972 after publishing her non-fiction book, Women and Sex, which railed against FGM and the sexual oppression of women.

The magazine Health, which had she founded a few years earlier, was closed down in 1973.

Still, she continued to speak out and write. In 1975, she published Woman at Point Zero, a novel based on a real life account of a woman on death row she had met.

It was followed in 1977 by the Hidden Face of Eve, in which she documented her experiences as a village doctor witnessing sexual abuse, “honour killings” and prostitution. It caused outrage, with critics accusing her of reinforcing stereotypes of Arab women.

Then, in September 1981, El Saadawi was arrested as part of a round-up of dissidents under President Anwar Sadat and held in prison for three months. There she wrote her memoirs on toilet paper, using an eyebrow pencil smuggled to her by a jailed sex worker.

“She did things that people just didn’t venture to do, but for her it was normal,” Dr Amin says.

“She wasn’t thinking about breaking rules or regulations, but telling her truth.”

After President Sadat was assassinated, El Saadawi was released. But her work was censored and her books banned.

In the years that followed, she received death threats from religious fundamentalists, was taken to court, and eventually went into exile in the US.

There she continued to level attacks against religion, colonialism and Western hypocrisy. She railed against the Muslim veil but also make-up and revealing clothes – upsetting even fellow feminists.

When BBC presenter Zeinab Badawi suggested during an interview in 2018 that she tone down her criticism, El Saadawi replied: “No. I should be more outspoken, I should be more aggressive, because the world is becoming more aggressive, and we need people to speak loudly against injustices.

“I speak loudly because I am angry.”

As well as sparking outrage, El Saadawi gained much international recognition, with her books translated into more than 40 languages.

“I know people do not always agree with her politics, but what inspires me most is her writing, what she has achieved and what that can do for women,” says British author and publisher Kadija Sesay, who acted as her agent in London.

“Especially if you are an African woman, or a woman of colour, you will be affected by her work.”

She received numerous honorary degrees from universities around the world. In 2020, Time magazine named her one of its 100 Women of the Year, dedicating a front cover to her.

But one thing would remain out of reach.

“Her only dream or hope was for some acknowledgement from Egypt,” Dr Amin says. “She said she had received honours worldwide, but never got anything from her own country.”

El Saadawi returned to her beloved Egypt in 1996 and soon caused a stir.

She stood as a presidential candidate in the 2004 election and was in Cairo’s Tahrir Square for the 2011 uprising against President Hosni Mubarak.

She spent her final years in Cairo, close to her son and daughter. As Egyptian newspapers reported her death, the simple message (in Arabic) “Nawal Al-Saadawi…….. goodbye” appeared on her Facebook page.

“She has been through a lot,” said Dr Amin. “She has affected generations.

“The young try to look for role models. She stands up.”

Kadija Sesay remembers the writer for her willingness to listen to other women’s stories and speaking to them about their harsh experiences.

“I don’t know many people, especially when thy are that well known, who are that giving,” she says.

“But she didn’t want to be anybody’s hero – she’d say, ‘Be your own hero’.”

_________________________