By José Pérez-Accino – National Geographic –

Christianity’s origins are found in many places, including Egypt, where Coptic Christianity flourished shortly after the death of Jesus.

Egypt, land of the pyramids, is the setting for many of the best known tales from the Old Testament. Through Moses, God punishes the Egyptian pharaoh for holding the Hebrew people in bondage. Betrayed by his brothers, young Joseph suffers in slavery in Egypt before rising to become vizier, second in power only to Pharaoh.

When turning to the New Testament, many people think of the lands of Israel and Palestine, the places where Jesus was born and preached. Egypt, however, also provides a key location in his story: a safe haven for the Holy Family. In the Gospel of Matthew, Mary, Joseph, and the infant Jesus flee from Jerusalem and King Herod, who wanted to kill the child. The family stays in Egypt until the danger has passed.

SAFETY IN EGYPT: In this detail of a 13th-century Coptic manuscript, the Flight into Egypt (top right) is depicted. This episode is of particular importance to Copts, who revere the places in Egypt where they believe the Holy Family wandered. PHOTOGRAPH BY AKG/ALBUM

In addition to its important place in Scripture, Egypt was a fertile garden in the early flowering of Christianity. From the first century A.D., as the faith took root and began to grow, Egypt became an important religious center, as theologians and scholars flocked there. Egyptian Christianity developed its own distinctive flavor, shaped by the words, culture, and history of ancient Egypt. This branch of Christianity would become the Coptic Orthodox Church, and its followers would be known as Coptic Christians, or, more simply, as Copts.

A Coptic stela from a fifth-century tomb in the Oasis of Al Fayyum. Coptic Museum, Cairo PHOTOGRAPH BY AKG/ALBUM

The name Copt has had a long journey. It comes from the European pronunciation of the Arabic word qibt, which derives from the Greek name for Egypt, Aigyptos. This in turn is derived from Hwt-ka-ptah, a temple in Memphis dedicated to Ptah. The Coptic language also arose from a blend of cultures, of Egyptian words written in Greek script. Several dialects evolved over the centuries, and many important Christian texts have been discovered written in Coptic.

Before Christianity became established, the existing religion of Egypt had roots reaching back millennia. After the golden age of Ramses II and his successors ended, Egypt underwent invasions by Libyans, Nubians, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans. Even so, Egypt’s old religion proved remarkably durable, partially due to its ability to absorb other influences. (See also: Rival to Egypt, the Nubian kingdom of Kush exuded power and gold.)

With few exceptions, invaders either adopted, or adapted, the venerable faith. The Nubians declared their loyalty to the Egyptian god Amun. In their admiration for Egyptian gods, the Ptolemaic dynasty (established by Alexander the Great’s general Ptolemy in 305 B.C.) created hybrid Greco-Egyptian gods such as Serapis.

Early beginnings

Christianity’s early traces can be found in the “Flight into Egypt.” Several sites in the country are associated with the Holy Family’s wanderings, including the Al Muharraq monastery in the Nile Valley in central Egypt. The monks believe the monastery’s Church of the Virgin is built where the family sheltered for a little more than six months during their time in Egypt. Another sacred site is in El Matariya, a suburb of Cairo, near the ancient city of Heliopolis. Tradition says that a sycamore tree, which became famous as the Virgin Mary’s tree, shaded the family during their journey.

According to Coptic tradition, the Christian church in Egypt was founded in Alexandria by St. Mark in the mid-first century A.D. Author of the second gospel in the New Testament, Mark became Alexandria’s first bishop and began spreading the teachings of Jesus. Historical sources support this claim. The Greek historian Eusebius, writing around 310, wrote in his Ecclesiastical History: “They say that this Mark was the first to have set out to Egypt to proclaim the Gospel, which he had written, and the first to establish churches in Alexandria.” (Read more about St. Mark: In the Footsteps of the Apostles.)

Other histories compiled about Mark recall his teachings as well as miracles credited to him. On arrival in Alexandria, Mark is said to have miraculously healed the hand of a cobbler, Anianus.

MIRACLE IN EGYPT In Alexandria Mark (left, at right) heals a cobbler, Anianus (seated), who converts and later succeeds Mark as head of the Egyptian church. Painting by G. Mansueti, 16th century. Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice, Italy PHOTOGRAPH BY AKG/ALBUM

Copts believe that Mark’s teachings attracted controversy and eventually led to his martyrdom around A.D. 68. The observance of Easter fell at the same time as a festival for the Greco-Egyptian god Serapis. Mark refused to worship the pagan god, and an enraged mob tied a rope around his neck and dragged him through the streets to his death. (See also: The Book of the Dead was Egyptians’ guide to the underworld.)

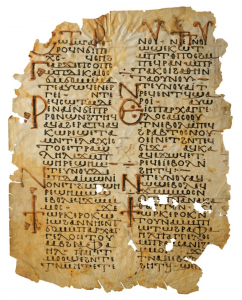

The final stage in the development of the ancient Egyptian language, Coptic emerged in the second century A.D., adopting letters from the Greek alphabet as well as retaining seven characters from the demotic, a simplified form of hieroglyphics. Pictured is a 10th-century Coptic codex containing an inscription about the archangel Raphael. Louvre Museum, Paris. PHOTOGRAPH BY SCALA, FLORENCE

A growing faith

Historians have long been fascinated by how quickly Christianity gained such a strong foothold in Egypt. One clue to its rapid spread may lie in Alexandria itself. In the very early Christian period, this city was a vibrant center of learning and philosophy. Throughout the third century, leading scholars of the world flocked there. Alexandria was also home to a large Jewish population, who might have been receptive to the teachings of Christianity. Acts 18:24-25 mentions a “Jew named Apollos, a native of Alexandria … well-versed in the scriptures … [who] spoke with burning enthusiasm and taught accurately the things concerning Jesus,” offering an insight into the growing Christian presence in the city.

Like Jerusalem, Antioch, and Rome, Alexandria was a leading center of early Christian thought. The School of Alexandria was the first Christian institution of higher learning, founded in the mid-second century A.D. Early leaders included St. Clement of Alexandria, who was born a pagan in A.D. 150, converted to Christianity, and became a leading spiritual thinker, teacher, and author. One of Clement’s pupils was Origen, whose A.D. 248 tract Against Celsus refuted pagan attacks on Christian doctrine and proved a crucial text in defending the new faith far beyond Egypt.

POWERFUL PRAYERS

Tombs in the Coptic necropolis at El Bagawat in the El Kharga Oasis in Egypt’s western desert. PHOTOGRAPH BY RENÉ MATTES/GTRES

As well as adapting symbols such as the ankh, Coptic Christianity may also have been influenced by ancient pharaonic liturgies. The revered fourth- and fifth-century monastic reformer St. Shenute decreed that novice monks should recite the following covenant:

I will not defile my body in any way, I will not steal, I will not bear false witness, I will not lie, I will not do anything deceitful secretly . . .

There is a striking parallel with the ancient mortuary texts known as the Book of the Dead, which took form around the 16th century B.C. In the long Negative Confession, the deceased must swear to Osiris the following lines: “I have not committed sin . . . I have not uttered lies . . . I have not polluted myself.”

Another noted Alexandrian thinker was Valentinus, whose interpretation of Christianity required believers to embrace divine knowledge—in Greek, gnosis. Gnosticism, as it came to be known, penetrated early Christian communities in Egypt, where its gospels, including the mysterious Gospel of Judas, seem to have been widely circulated. (See also: Gospel of Judas Pages Endured Long, Strange Journey.)

In a period when paganism and Christianity coexisted, there was cross-pollination between the two. The ancient Egyptian symbol for life, the ankh—a cross shape with an oval loop—influenced the development of the cross known as the crux ansata, used extensively in Coptic symbolism. Even so, Christianity advanced in the fourth century. In the early 300s the city of Oxyrhynchus had 12 pagan temples and two churches; a century later, the situation was reversed.

Egypt was also the site of another important development in Christianity: monasticism, a practice born in the deserts of Egypt. Imitating Jesus’ wanderings in the wilderness, holy hermits underwent extreme privations to deepen their faith. The most famous of the Desert Fathers was St. Anthony the Great. His visions, in which the devil appeared to him in the guise of a pious believer or a beautiful woman, had a profound effect on Christian notions of the devil. (See also: St. Anthony’s Fire, the killer in the rye.)

Periods of persecution

A Coptic child’s tunic (date unknown). National Museum, Ravenna, Italy PHOTOGRAPH BY BRIDGEMAN/ACI

Between the first and fourth centuries, the Roman Empire unleashed a series of persecutions against Christians. The most savage measures were passed under Emperor Diocletian in 303, which resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands of believers. According to tradition, one victim during this period, which Copts call the age of martyrs, was St. Catherine of Alexandria. The daughter of the governor of Alexandria, she challenged the emperor Maxentius, who had her tortured. When he ordered her execution, the spiked wheel she was to be killed upon broke when she touched it. After the Edict of Milan in 313, the persecutions stopped, and Christians could worship freely. By 380 Christianity (based on the principles established at the Council of Nicaea) became the official faith of the empire.

Theological differences strained the early church, and Egypt’s Christians found themselves at the forefront of these conflicts. In the fifth century church leaders began to debate whether Jesus could be both mortal and divine. In 451, 520 bishops met at the Council of Chalcedon to consider the matter. The debate split the church into factions, beginning a rift that would separate the Copts from other branches of the Christian faith.

The Virgin Enthroned holds Jesus on her lap and is surrounded by the Apostles in this fresco decorating a painted niche at the Bawit Monastery south of Cairo. Founded by a holy hermit around A.D. 385, the monastery declined in the ninth century, but its iconic, vibrant artworks remain. PHOTOGRAPH BY DEA/ALBUM

For the next two centuries the Egyptian church blossomed, attracting more and more followers. The revered fourth- and fifth-century monastic reformer St. Shenute built a lasting legacy of learning and piety at the monumental White Monastery in present-day Sohag on the west bank of the Nile. Its colossal library of Coptic texts was the marvel of the Christian world. At its peak there may have been as many as 4,000 monks and nuns living there.

Egypt’s position at the crossroads of the African and eastern Mediterranean had always been coveted by invaders, and in 642, Alexandria fell to the Arab invaders, bearers of the new Muslim creed. Although the new regime initially tolerated the church, the population began steadily to convert to Islam. Coptic Christianity held fast as the faith of Egypt changed again. Today, it is estimated that some 10 percent of Egyptians practice the Coptic faith, led since 2012 by Pope Tawadros II, the latest in an unbroken line of patriarchs believed to stretch back to the Gospel writer St. Mark.

__________________________________________

Top photo: Frescoes of Jesus, the Virgin Mary, the Apostles, evangelists, prophets, and angels adorn the walls of the church of the Red Monastery, built in the late fifth century A.D. as part of the flowering of Coptic culture in Egypt. PHOTOGRAPH BY PEDRO COSTA GOMES