By The Wall Street Journal –

Copts face increasing threats under a regime they once hoped would make them more secure.

MINYA, Egypt—Egypt’s Coptic Christian minority is facing a surge in sectarian attacks, with increased instances of violence and threats from Muslim neighbors forcing churches to close and casting a pall over Orthodox Easter on Sunday.

In one recent incident that echoed many others, residents of central Egypt’s Sohag province were seen in a video recorded earlier this month and reviewed by The Wall Street Journal beating their male Coptic Christian neighbors with sticks as women screamed, leading to the shutdown of a local church, according to Coptic groups and a human- rights organization that documented the incident.

Nowhere has the assault on Copts been worse than in Minya province, some 130 miles south of Cairo on the western bank of the Nile, the site of at least three mob attacks on Coptic churches since August. On Jan. 11, a crowd waving wooden clubs jeered at a group of Copts as they fled in a pickup truck through narrow streets. “Leave! Leave!” the crowd chanted, as seen in a video filmed by residents and corroborated by church officials. The Coptic church in the village was closed indefinitely. The month before that incident, a police officer shot dead a Coptic man and his teenage son following a dispute, triggering angry protests by Christians in the area. The officer was sentenced to death earlier this month for the killing.

Popular assaults on Copts are rising against a background of shootings and bombings by militant groups like Islamic State, which have killed more than 140 Egyptian Christians since 2015. Such attacks were virtually unknown before January 2011, when 23 people worshiping in an Alexandria church were killed in a bombing.

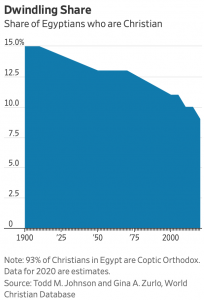

Such violence has compelled tens of thousands of Copts to leave Egypt since 2011. The exodus amounts to a continuing crisis for the Middle East’s largest Christian community, which comprised 10% of Egypt’s population in 2015, according to the CIA World Fact Book. Copts who once expressed hopes for improvement under the nominally secular regime of President Abdel Fattah Al Sisi say their situation is worsening instead.

Christians remain shut out of the highest echelons of Egypt’s government and say they have no place in the senior ranks of the country’s security services, leaving them feeling unprotected from growing violence in their towns and villages.

“Egypt is suffering from terrorism, but sometimes Copts feel they are paying the price more than others,” said Bishop Makarios, the head of the Coptic diocese in Minya.

Copts have been the target of violent attacks since the 1970s, when President Anwar Sadat turned toward Islam, souring what had been generally civil relations between the state and the church. Attacks increased following the 2011 revolution that ended the 30-year dictatorship of President Hosni Mubarak and led to a breakdown in state control in parts of the country.

Today the attacks represent a sensitive challenge for Mr. Sisi, who came to power following a military coup in 2013 and vowed to defend the Christian minority. Mr. Sisi has won plaudits from the Trump administration for promoting religious pluralism, but Coptic leaders say they remain under siege.

Dwindling Share of Egyptians who are Christian

Source: Todd M. Johnson and Gina A. Zurlo, WorldChristian DatabaseSource: Todd M. Johnson and Gina A. Zurlo, World Christian Database. Note: 93% of Christians in Egypt are Coptic Orthodox.Data for 2020 are estimates.

In 2016, Mr. Sisi’s government passed a law preserving restrictions on the construction of churches, rejecting calls from some civil-society groups to allow places of worship to be built freely. Construction of new churches is often a spark for violence in rural Egypt. State institutions forced 22 churches to close since the law came into force the same year.

Since the passage of the law, 32 incidents of sectarian violence against Copts have taken place, according to the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, a human-rights group based in Cairo, a considerable increase from the number it documented in the first two years of Mr. Sisi’s presidency.

Copts say the Sisi government has failed to make a concerted effort to confront widespread bigotry among the Muslim-majority population in Minya, an impoverished agricultural region where many people begin working at a young age and 37% of the population is illiterate.

Copts and rights groups also blame the security forces for normalizing a pattern of sectarian attacks. Following each recent mob attack in Minya, security forces asked Copts to sit down for informal so-called reconciliation sessions with their attackers, rather than pursue prosecutions, Bishop Makarios said. No suspects were detained in the Jan. 11 incident, in which 1,000 people joined the mob, according to the Minya Coptic Orthodox Diocese.

“Every time, extremists are able to impose their demands,” the diocese said after the Jan. 11 attack.

A spokeswoman for the Minya governor’s office declined to comment on the event but didn’t challenge the church’s account of the attack, which was also captured on video.

The continuing violence has tarnished the record of Mr. Sisi, who has embraced opportunities to portray himself as a protector of Egypt’s Copts ever since he led the 2013 coup that deposed Islamist President Mohammed Morsi.

On the Coptic Christmas Eve, Jan. 6, Mr. Sisi inaugurated a giant cathedral in Egypt’s new administrative capital, eliciting a laudatory tweet from President Trump: “Excited to see our friends in Egypt opening the biggest Cathedral in the Middle East. President Al Sisi is moving his country to a more inclusive future!” Mr. Sisi has made a point of regularly attending a Coptic Mass on Christmas Eve, a first for an Egyptian president,

But Egypt’s president has ignored calls from parliament and civil society to establish an independent commission to fight discrimination, as required by Egypt’s 2014 constitution. Mr. Sisi and his government hasn’t issued a decision on the mandated commission, giving no public explanation.

A spokesman for Mr. Sisi didn’t respond to a request for comment on the Coptic church’s concerns. “In Egypt, we do not discriminate based on religion,” Mr. Sisi said in a speech in November. “Whether they are Muslim or Christian, in the end they are just Egyptian.”

The increased attacks in recent years have crushed the hopes expressed by many Copts that the military’s removal of Mr. Morsi would reduce their marginalization in Egyptian society. Instead, hard-line Islamists blamed Christians for the military takeover, prompting dozens of attacks on churches around the country.

In Minya, Copts say relations have continued to deteriorate. In November, Islamic State gunmen opened fire on buses carrying Coptic pilgrims to a remote monastery in Minya, killing seven people. The attack took place on the same desert road as a nearly identical shooting in May 2017 that killed 28 people, sparking outrage among rights advocates and Copts who blamed the state for failing to secure the area.

“When I saw the car chasing us, I was in disbelief because this happened before. Same pattern, same type of people, same location,” said Aida Shehata, 37, who survived the shooting in which her husband and teenage daughter were killed. “What has the government done since then? Nothing.”

_______________

https://www.wsj.com/articles/anti-christian-violence-surges-in-egypt-prompting-an-exodus-11556290800

By Amira El-Fekki and Jared Malsin