By Jerome Drevon and Nanar Hawach – Foreign Affairs –

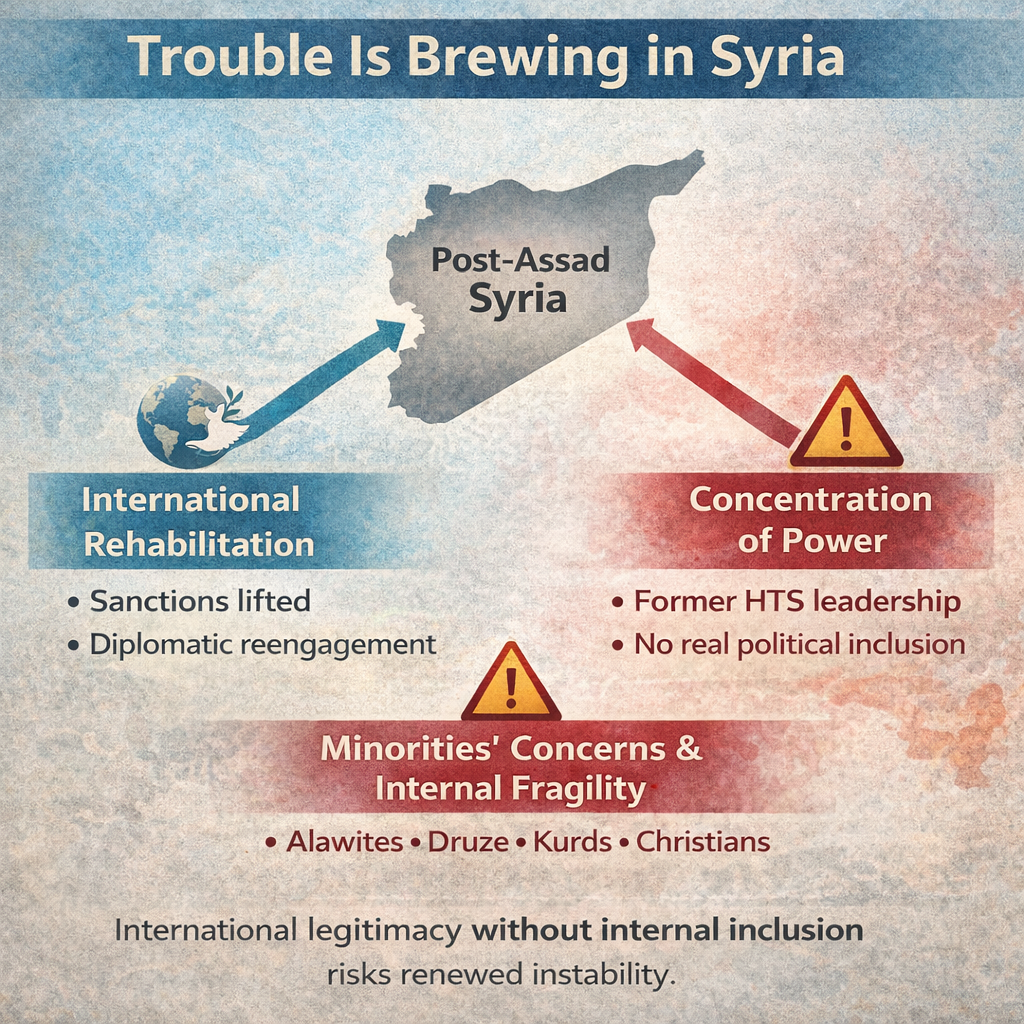

In little more than a year, Ahmed al-Shara—a former al-Qaeda commander—has overseen one of the most dramatic political reversals in the modern Middle East. After the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s half-century-old dictatorship in late 2024, Shara emerged as Syria’s leader and rapidly secured the country’s rehabilitation on the international stage. Western and Arab states lifted or suspended sanctions, pledged billions in reconstruction assistance, restored diplomatic relations, and welcomed Damascus into regional forums. Syria even joined the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State (ISIS).

International Rehabilitation Without Precedent

This turnaround was once inconceivable. When Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the group Shara led until its dissolution, entered Damascus, Syria was a pariah and HTS was listed by the UN Security Council as a terrorist organization. Shara and Interior Minister Anas Khattab were personally sanctioned for their past ties to al-Qaeda. Yet within months, Damascus reassured foreign capitals on their key concerns: countering ISIS, dismantling chemical weapons remnants, curbing Iranian influence, preventing foreign fighters from exporting violence, and stabilizing Syria’s borders. With diplomatic backing from Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey, these commitments led to rapid sanction relief. In November 2025, the UN delisted Shara and Khattab, clearing the path for full diplomatic engagement.

Syria’s new leadership also managed difficult regional relationships with restraint. It preserved cooperation with Russia, dismantled Iranian-aligned militias without provoking direct confrontation with Tehran, severed Hezbollah’s overland supply routes, and avoided escalation with Israel despite repeated Israeli airstrikes and incursions. Apart from Israel, Damascus now faces no major external antagonist, and no power appears willing to sponsor armed opposition.

Consolidation of Power at Home

Yet these diplomatic successes mask growing domestic problems. The very methods that enabled Shara and HTS to win the war—tight command structures, ruthless pragmatism, and centralized authority—are now hindering Syria’s political transition. One year into the post-Assad era, power remains concentrated in a narrow circle of former HTS leaders who have yet to articulate a credible, inclusive vision for Syria’s future.

Shara’s early domestic achievements were real. He oversaw the dissolution of dozens of armed factions, including HTS itself, and their formal integration into a single national army in January 2025—without triggering large-scale internal conflict. Rather than negotiating with factions collectively, he co-opted individual commanders through senior appointments, denied promises of territorial autonomy or political representation, and prevented rival power centers from emerging.

At the same time, the new authorities refrained from imposing a hard-line Islamist agenda. Instead, they emphasized rebuilding state institutions and initiating a constitutional process. The transitional government appointed in March 2025 appeared more diverse than expected, incorporating technocrats, civil society figures, and members of the diaspora. The cabinet included figures such as Raed al-Saleh of the White Helmets and Hind Kabawat, a Christian activist—an unprecedented inclusion given HTS’s earlier rejection of women’s political participation.

A Façade of Inclusiveness

Beneath this surface, however, authority remains highly centralized. Former HTS figures dominate the presidency, the security apparatus, and key ministries. All political parties were dissolved in January 2025, and no framework exists for forming new ones. Former HTS members effectively function as an informal ruling party, even when lacking official titles.

Parliament, selected through a tightly managed process overseen by committees appointed by Shara, holds limited power. Women remain severely underrepresented, occupying just six of 119 seats. Many Syrians therefore fear they are not witnessing a transition toward pluralism but the consolidation of a new authoritarian system—one that is internationally accepted but domestically unaccountable.

Security Failures and Communal Tensions

These political concerns are compounded by security failures. Syria’s new army remains fragmented in practice, struggling with weak discipline, limited resources, and sectarian divides. In several instances, deployments meant to restore order instead exacerbated tensions. In March 2025, government-aligned forces killed roughly 1,400 Alawite civilians during operations against pro-Assad insurgents on the coast. In July, a poorly managed intervention in clashes between Druze and Bedouin militias in Sweida was widely perceived as favoring one side, pushing Druze leaders—including previously moderate ones—toward demands for autonomy and even appeals to Israel.

Although the government has announced investigations and some corrective measures, meaningful accountability remains uncertain. Criminal networks and nonstate armed groups continue to operate across the country, engaging in kidnappings, extortion, and killings. Minority communities are particularly vulnerable, but insecurity affects Syrians broadly. Each failure reinforces suspicions that the emerging state serves a narrow constituency rather than the population as a whole.

The Kurdish Question

Uncertainty has been especially acute in the Kurdish-majority northeast. For more than a year, negotiations between Damascus and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) stalled over autonomy and integration. Kurdish leaders feared submitting to a centralized system dominated by former jihadists and lacking institutional checks.

Recent developments offer cautious optimism. After government forces took control of most former SDF territory, an agreement was reached outlining the SDF’s integration into the national army and recognizing Kurdish cultural and linguistic rights. These steps ease immediate tensions but stop short of clarifying the political system Kurdish communities—and others—will ultimately be asked to join.

_____________________

Summarized from this full essay: