By Le Figaro Magazine –

After traveling across Europe to uncover the mysteries of faith and monasticism in the High Middle Ages, the writer Romain Sardou set out in search of the “Unknown Monk,” the very first of them all.. in Egypt’s desert.

Every journey to Egypt should begin at the Church of Saint-Roch in Paris. It was there, in 1809, that one of the most improbable singular points in the history of human genius occurred. Kind of Science fiction!

Let’s say it plainly: to reduce Egypt’s ancestral glory to its pharaonic dimension alone is the laziness of a travel agent. Moses was Egyptian. Jesus spent his early years in Egypt. It was in Lower Egypt that faith and philosophy, the Bible and Greek thought, Plato and Christ, were first brought together by Alexandrian thinkers—giving birth to… us!

The first hermit in Christian history? From Egypt. The first monk? Egyptian. The first monastery? Also in Egypt. In the shadow of its stone pyramids, this country raised “spiritual” pyramids that are far too often neglected in connection with our Christian heritage.

On these red and black African lands, a decisive turning point emerged among the first disciples of Jesus of Nazareth. Just as the Jewish people had their Prophets, it was the honor of the Church to give birth there in Egypt to its great Solitaries.

From my hotel room in Cairo, I can see the Nile, surely the most dreamt-of river of my youth. “In the rich silt, the ears of grain had sprung up like javelins…” The Romance of the Mummy—remember that? This morning, for the end-of-Ramadan celebrations, the only thing one notices in the jubilant streets is children everywhere. It feels like Paris. In the 1950s… Or Alexandria. In the 2nd century!

Baptized Socrates

Alexandria was then the intellectual center of the Roman Empire. From this Egyptian capital, we know of its lighthouse, a wonder of the world. We know of its library, a wonder of humankind. But do you know about its School?

This theological institution, originally conceived for the training of the first priests (the Church was then in its infancy, with everything still to be accomplished), would shape the fifth generation of Christians after Jesus—the first to question their faith with increasingly existential inquiries…

But where did these Alexandrians seek arguments, methods, and keys to better structure their thoughts and respond to their opponents? From the ancient Greeks! Thus, little by little, took place the extraordinary synthesis of Greek philosophy and nascent Christianity. Rarely have debates been so decisive for the centuries to come.

So let us state it clearly: it was not Greek thought that shaped our present modernity, but Hellenized Christian thought! We are less the children of Athens than of Alexandria.

In this city filled with “Christian Socrates,” a man leaves everything behind. We know nothing about him—least of all his name. (For convenience, let us call him Alpha.) He yearns to live “in the spirit of the Gospel.” He sets out to encounter divine contemplation in peace, with the sense that God is more inclined to visit those who are alone. And since solitude lends itself to a face-to-face encounter, he goes into the desert.

Among his Christian companions, he has no predecessor. He has no example to follow. There is no tradition to guide him in his endeavor. At that time, there was an old Syriac word that roughly meant “without a woman,” a “bachelor” or “alone”: ihidaya—monk.

Between Tatooine and Arrakis

Joseph Conrad wrote: “One must be a saint to live in the desert.” I rather think one must live in the desert to become a saint… In any case, it was in these Egyptian lands of the 3rd century that Christians opened this chapter of their history: believers setting out in search of their own perfection. After our mysterious monk Alpha, the pioneer of pioneers, how many brothers Beta, Gamma, Delta followed during this monastic dawn? And then one day, at last, a name was remembered! A perfect hermit, he would become THE monk before the monks, just as Adam, in Paradise, had been the man before men.

His name is Paul, he is noble and educated, he is 16 years old and, around the year 250, fearing that he would be denounced as a Christian to the Romans of Thebes, he fled into the desert to save his faith and his life. No divine illumination, no heavenly message, no dramatic calling: Paul was avoiding danger, as any one of us would have done.

He found refuge in a mountain cave in the Eastern Desert, where Cleopatra’s money counterfeiters had once dug their mines. He likely thought he would hide there for a while—just long enough for the imperial threat to fade… In reality, Paul would remain in that cave for the next ninety years of his life, never seeing another person again!

Today, on the road to the great monastery built above the place of his retreat, along the shores of the Red Sea, I come across vast fields of wind turbines stretching as far as the eye can see. Such is the way of things… Today’s Don Quixotes are those who erect the windmills!

Brother Ephrem welcomes us to Saint Paul of the Desert (Anba Paula). It is a sand-colored monastery, set in an arid landscape south of Zafarana. There reigns a stony calm, the same that must have weighed upon young Paul when he first settled here.

Our saint conceived a love for this dwelling marked by the hand of God…

—Saint Jerome

Upon entering the cave that served as his shelter, my emotion is twofold. I had known of this place long before having the privilege of visiting it, having read its description in Saint Jerome and in Arnauld d’Andilly: “Our saint conceived a love for this dwelling marked by the hand of God…”

Saint Paul’s holy cave measures barely a few square feet. Coptic monks conduct services there in Coptic and Arabic, very close to the saint’s tomb. When the young Theban first arrived, only a spring and a palm tree allowed him to soften the harshness of his exile.

It is in this setting—somewhere between Tatooine and Arrakis—that the miracle takes place… Understand this: one is not born a monk; one becomes one. Except for Paul of Thebes.

Here, we must apply the most important word to attempt to grasp the meaning of a monk’s life—whether in the past or today: Paul was not a “divided” being.

There was no trace of dolorism in him, no willful embrace of suffering. He knew neither affliction, nor the urge to wander, nor the lacking of human contact. He had no need to struggle against demons—not even those of lust. He knew nothing of the fractures, battles, and inner tensions that a monk endures throughout his ascent toward God.

Anger, resentment, gluttony, pride—none of these tore at him. Just as Athena emerged fully armed from the head of Jupiter, he entered his cave fully virtuous. To put it in Jung’s psychological terms, he was a man without a shadow.

The Holy Ladder

He stands before us, his heart purified, his intellect illuminated, his soul at peace. Humanity’s degree zero before God, he challenges us—us, whose exasperation is always just one tweet away from hysteria. As men of the masses, we are no longer merely divided, we are shattered!

I can’t help but smile at today’s purveyors of “well-being” and “coached living,” selling us unity tips that Saint John Climacus was already offering in the 7th century in his Ladder of Divine Ascent—a masterpiece of inner transformation!

And our Paul of the Desert stands, by his very innate nature, at the summit of that ladder. The first exemplary hermit, he would remain without example. The legion of monks—this spiritual militia that would follow him down to our own day—would always consist only of brothers far less gifted than he in the living wisdom.

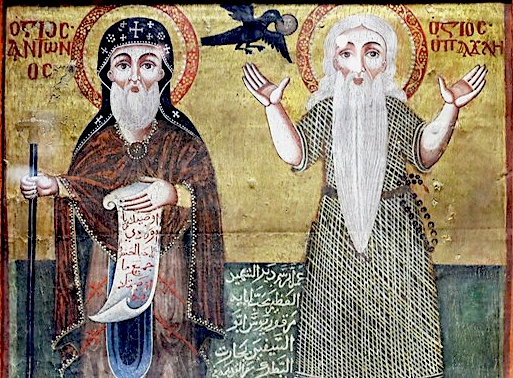

It’s curious—everywhere he is depicted, such as on the walls of his small cave in Egypt, Paul appears as an old man, with his long beard reaching down to his knees, his tattered garments woven from palm fibers, and his deeply furrowed brow…

Yet to me, he is always the sixteen-year-old youth, the one who so brilliantly turned necessity (fleeing the Theban region) into will (prolonging his solitude until the Absolute). I can only imagine Paul as a noble young man full of promise—a young explorer of human nature.

Educated, he was familiar with the heated debates among Christians before his flight. To read Origen and Clement of Alexandria, the great heads of the School of that time, is astounding. Any man or woman today seeking meaning in life would find in their writings lines of reasoning they would never conceive alone. (Their ancient faith should not deter you from reading them: it is simply another way of questioning oneself—perhaps the most humble way that ever existed.)

Paul took no books with him. No doubt it was enough for him to keep in memory the Jewish legacy of the Psalms, the mother tongue of Christianity. He did not work. For thirty years, his palm tree fed him exclusively with dates, until God sent a raven that brought him half a loaf of bread each day… He drank from his small hillside spring, now closed to visitors, but which Brother Ephrem allows me to approach.

In the evening, at the monastery, once the tourists and pilgrims have gone, I realize how fortunate I am to be able to spend my night so close to those of Paul.

Up to now, I have taken you in France in the footsteps of Saint Martin, in Ireland with Saint Columban, and in Italy with Saint Benedict. Here, they all come together. They all know… And yet, during Paul’s lifetime, no one suspected anything. No one knew him. No one guessed where he was. No one!

Meanwhile, another Egyptian, born in a village of the Nile Valley at the time when Paul was leaving Thebes, the son of a good Christian family, found himself orphaned of both father and mother around the age of 20, in 271, with the responsibility of a very young sister. While wondering what to do with his inheritance, as the Gospel was being read in a church, he heard the Lord say to the rich man: “If you want to be perfect, go, sell all that you have and give it to the poor. Follow me!” He took this word as a personal oracle.

Saint Anthony the Great was born that day.

The Temptations of Anthony

From the very start of his conversion, one can see what sets him apart from Paul. Having given away his possessions and placed his sister safely in a community of virgins, Anthony sought out an old ascetic who lived not far from his village. (The monk Epsilon, Zeta, or Eta of our lineage?)

In search of a model to learn the life he should lead, Anthony took on several mentors, always in the outskirts of towns, each devoted in his own way to prayer and abstinence.

Curious about everything, he viewed asceticism as a craft in which the hermit must strive for perfecting. But he did not have Paul’s “graces”: Anthony was the target of endless temptations, constantly at risk of being “divided.” Tradition tells that the devil himself took advantage of this. The famous temptations of Saint Anthony are well known! Artists have depicted, in every possible shade, the assaults on his weakness: naked women, dragons, mountains of gold, appetizing dishes, and at times, unbearable humiliations and tortures…

Anthony is a laborer on the monastic path; his journey toward God is a constant battle. His unity, he wins victory after victory, almost hour by hour, driven by zeal for virtue. He is a monk like any other because he is a man like any other—that is precisely why he will become the most exemplary of all: the Abraham of monks. Paul is the destination. Anthony embodies the journey.

Moreover, this ascetic traveled extensively, working to earn his bread and to give to those in need. Leaving his home, he first lived in a tomb, then withdrew to an abandoned fortification before venturing further into the desert—first to Mount Pispir, then to Mount Quolzoûn, in this eastern part of Egypt’s Eastern Desert, identical to that of Paul’s refuge, which he didn’t know about. There, he withdrew into a cave carved into the cliff, continually striving for perfection and better escaping the disciples who burdened him with their devotion by following him everywhere.

During this retreat, as a supreme gift of grace, he began to perform miracles—always under the relentless and watchful eyes of furious demons…

The Ultimate Cave

After leaving Saint Paul of the Desert, I arrive at the Monastery of Saint Anthony, home to the famous ultimate cave. That very evening, I climb alone the steps leading to the sanctuary built into the cliffside. The last time I was this exhilarated climbing a staircase for hours was during the ascent of Masada!

You have to bend over double to enter Anthony’s cave. Here, it is not like the caves of Saint Benedict at Sacro Speco, Saint Martin at Marmoutier, or even Paul’s: pressed against the walls, with no light at all, you feel crushed by the mountain. In the spot where Anthony prayed, it is impossible to stand upright. One minute in this silence will either weigh you down or carry you away, suffocate you or bring you relief—depending on your relationship with peace. You must know how to live there as if you were to die each day… or else leave very quickly.

Emanuele Scorcelletti

Tradition has remembered this powerful figure of Anthony and crowned him with the title of “first (or father) of the monks.” Historians know this is untrue. Saint Anthony of the Desert is not the first monk—he is the first monk to have been placed in the spotlight. He is less famous than his biography, written in Greek by Athanasius the Great, who would leave Egypt to convert the whole of the West to the monastic spirit.

Saint Paul of Thebes is not the first hermit in history either. But his predecessors did not have the chance of having Saint Jerome spread their biographies!

“A monk better than you!”

One day, the aged Anthony speaks to God from his cave and, in a moment of pride, asks Him whether he might not be the most advanced monk in the desert, the one farthest removed from the rest of mankind. But the Lord answers no, and reveals to him the existence of another nearby monk, “better than him.”

Perplexed, Anthony sets out. After only a few hours’ walk, he finds the very, very old Paul. The latter, who has not seen a human face since the age of sixteen, is about to die.

Nothing is more moving than the meeting of these two leaders of monasticism. Anthony burying Paul is monastic brotherhood under the gaze of the angels — eremitism and cenobitism united. It would take the film director George Stevens to bring that back to life!

All his life, Anthony was followed by great numbers of disciples. Some of these followers, such as Pachomius and Macarius, went on to establish enclosed communities and rules of life to enable a new form of asceticism: the “common” life of prayer. Thus, Christian monasteries were born from the fervor that surrounded Anthony…

I visit one of them, the oldest, Saint Macarius of Scetis, with its seven churches. The spiritual sons of Anthony and Paul are still there… But for what future?

Today, much is said about artificial intelligence and augmented humanity. (If transhumanism were to come; a sudden obsolescence threatens Homo sapiens.)

Yet it is conceivable that some humans will resist the advantages of such progress, and that the very last “physiological” holdouts will be… our monks. Just as they are now a living repository of Antiquity, they will become a repository of ancient humanity. With their bodies inviolate, they will return to the deserts to become Pauls and Anthonys once again. And, most certainly: always in Egypt! Since everything leads us back to that land…

An Egyptian under Bonaparte

Paris. Spring 1809. A very young man pushes open the doors of the Church of Saint-Roch, in the center of Paris (not far from the Louvre). He asks for the vicar—a Coptic priest who had come to France in an exceptional way, following Bonaparte’s Egyptian campaign.

The young man is interested in the Coptic language as the last living descendant of ancient Egyptian. He studies it diligently, convinced that the Coptic of his time still preserves the vocabulary, roots, and structures of the language spoken by the pharaohs.

His name is Jean-François Champollion, and his encounter with Father Yuhanna Chiftichi at Saint-Roch will hasten his deciphering of the hieroglyphs!

Suddenly, the entire universe of the Ramses, silent for millennia, awakens and speaks again—thanks to a child of the French Revolution and to Coptic Christians of the 5th century who, by making their liturgy independent from Rome and Byzantium, froze their language for centuries.

This superimposition of such contrasting eras is dizzying—like a temporal fault where the cult of Raa, the psalms of Late Antiquity, and the Napoleonic spirit coexist… It is not a journey through time, but rather times themselves traveling to Champollion. I told you, this is science fiction!

And all of this, perhaps, because a certain monk Alpha once decided to leave Alexandria and give up everything to pray and chant psalms in his own secluded corner? Him or another—history must always honor the great unknowns. Pax.

________________________________

Edited translation of: